Time on the Water

Figure 1: Time on the Water

We humans are obsessed with “time” – and we always have been. The earliest evidence of time keeping goes back as far as 20,000 years as early man attempted to keep track of the lunar cycle. By 4500 BCE the Egyptians had developed yearly calendars in order to predict the anuual flooding of the Nile. They also developed the sundial to keep track of the time of day. Babylonian civilization which flourished around 2000 BCE divided the day into 24 hours with each hour divided into 60 minutes, and each minute into 60 seconds. It is the Babylonian division of the day which gives us our modern units of time. [1]

The Greeks actually has had two words for time: Chronos which signifies the passing of time as would be measured by a clock and Kairos which represents time in the moment. [2]

St. Augustine, around the end of the 4th century CE brought Greek philosophy (especially Plato) into Christianity. Still, the concept of time puzzled St. Augustine who stated:

“What then is time? If no one askes of me, I know; if I wish to explain to him who asks, I know not.”

Are we still obsessed with time? Very. According to the Oxford English Corpus “time” is the most common noun used in the current English language!

When not asking for time we are tracking time, serving time, buying time, killing time, having a good time, taking a time out, bedtime, nighttime, good times, bad times, free time, and lunch time among many others. [3]

What does this have to do with our nautical endeavors? Everything. If anything, we have become more dependent on time than ever before.

Time and Navigation

Let’s fast forward past Galileo and Huygens and their pendulum clocks to the fateful year of 1707 when the British Admiral Sir Clowdisley Shovell sailed his fleet directly onto the Scilly Isles, during which he lost approximately 2,000 men.

Figure 2: Isles of Scilly

In response to this tragedy, Parliament established the Longitude Act of 1714. A prize of over a million US dollars in today’s money was offered to anyone who could devise a method to accurately calculate longitude at sea. Latitude was already available by taking a sighting of celestial objects and in fact the typical approach to sail from England or Spain to the New World was to sail south to the latitude of your destination and follow that latitude west until you reached land. But as we saw above it was not very reliable. If you are at sea you want to know exactly where you are – and that means both latitude and longitude.

One solution was a very accurate chronometer or “time” piece a.k.a. watch. How would that help? Well, it is very straightforward. The earth rotates 360 degrees [4] each day and if we divide 360 by 24 hours in a day that means that each hour the earth rotates 15 degrees. So, if you are at sea at noon (12:00) and the sky is clear, you can obtain a midday sighting of the sun. By doing that you have established your latitude. But in addition, if you have an accurate watch set to Greenwich Time when you departed, and your watch reads 16:00 then you know you are 4 hours west of Greenwich. Four hours is 60 degrees of longitude (15 x 4) and therefore you are 60 degrees of longitude west of Greenwich.

That’s it, all you require is an accurate chronometer. And that was how John Harrison (1693-1776) won the prize. He was such a skilled craftsman that he produced a series of chronometers (H1-H4) that were immune to the rocking and rolling of the ship and also to changes in weather temperature and humidity.

Figure 3: H1 early version

Figure 4: H4 final version and ready for sea

So, once you had an accurate chronometer which was time-set to your port of known longitude you could – with a sextant reading for latitude – establish your position. One didn’t need to use Greenwich as the standard as long as you knew the exact longitude of your home port. It could for example be Boston in the United States; but then everywhere else would be related to Boston longitude.

The standard became Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) which later became Universal Coordinated Time (UCT), [in the military it is referred to as “Zulu Time”, more on that below] based on the location of the British Naval Observatory in Greenwich, near London. [5]

For all of the 19th and much of the 20th century this is where we stood. Accurate time for longitude + sextant for latitude = a fix and then DR (Dead Reckoning) until the next fix.

Enter Global Positioning System (GPS). GPS is made up of a network of a minimum of 24, but currently 30 satellites placed in orbit by the U.S. Department of Defense. It was originally developed for use by the US military but by the 1980s the system was allowed to be used for civilian purposes worldwide. GPS reception requires an unobstructed line of sight to four or more satellites. The system has three parts: satellites, ground stations, and receivers.

Figure 5: The 3 components of GPS. The Ground stations ascertain the location of each satellite. Each satellite sends out a signal and since speed x time = distance and since the speed of the broadcast is fixed the time it takes to get to your receiver will tell you the distance from that satellite.

Satellites act like stars in a constellation. We know where they are supposed to be at any given time. The ground stations use radar to confirm that they are there. The receiver in your boat or phone listens for the Radio Frequency Broadcast signals and determines how far away they are based on the time it takes to get to your receiver. At the speed of light, a signal from a satellite directly overhead would take 67 milliseconds to reach earth. And your receiver will listen for the signal from at least 4 satellites at once. It calculates the distance (range) of the satellites, and since it knows the position of each it can “trilaterate” your position to within a few yards / meters. The fourth satellite allows the receiver to figure out the altitude. Higher tech receivers have a definition to a few inches. If you leave your receiver on it can stay in contact with the satellites and tell you the following:

How far you have traveled

How long you have been traveling

Current speed

Average speed

ETA if you maintain current speed

So, aside from the fact that all electronics may fail for one reason or another is there any reason to doubt the GPS signal. The answer is yes. In 2019 a British oil tanker was lured into Iranian waters in the Strait of Hormuz when its GPS was “spoofed” by the Iranians. It told the tanker that it was in international waters when it was not, and the ship was captured, and its crew imprisoned for 2 ½ months. Drones have been known to interfere with GPS accidentally or maliciously; the system is vulnerable. Hacking the system has never been easier. Protecting it is the responsibility of the Secretary of Transportation. Three separate laws require the US government to provide backup to GPS – but no funds were ever appropriated [that sounds about right]. There are a number of technologies which could be used and hopefully the government will allocate the funds soon. Nevertheless, as discussed in Chapter 2 and in the prior articles on navigation, attention to “natural navigation” is an important backup to total reliance on electronics. I’m not recommending you “go” natural, rather that you “know” natural.

Clocks, clocks and more clocks

Up to this point we have discussing time within a Newtonian framework: distance = speed x time. But we live in a post Einsteinian and post quantum world where time is treated very differently. The concept of time preferred by physicists is beyond the scope of this discussion and let’s just say that it gets very speculative. There is nothing, for example, in modern physics to preclude time travel – real “Back to the Future” time travel – not the kind we will be discussing in the following article. It all gets kind of wonky, and you know things are wonky when the physicists start hanging out with the philosophers.

Time – for the sailor and other humans – is wonky as well but for a different reason – evolution. We inherited a brain that really only cared about keeping track of each day [“to live another day”]. In fact, there are really only 3 natural time “clocks” in nature – the day, the lunar month, and the year.

Virtually all living things on earth possess daily clocks that keep them on a 24-hour cycle – bacteria, fungi, flowers, plants, trees, and all animals including us. Whether you are diurnal as we are, or nocturnal such many owls and bats the clock runs on a 24-hour cycle. And when nature found a good gene that worked, it was not embarrassed to reuse it. An example is the Period gene, which was identified in the Drosophila fly in 1971. It is one of many clock genes that we share with the lowly fly. Heck, we share 50% of our working genes with a banana!

For a full discussion of our circadian rhythm, please see Chapter 12 entitled “Sleep” in Healthy Boating and Sailing. The master clock is in our brain in an area of the hypothalamus known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). (Figure 6)

Figure 6: The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (SCN)

That has been recognized for some time. But only in the last 20 years or so has it been shown that each of our internal organs has its own intrinsic clock with its own schedule of on time and off time. And we should think of these clocks as forming a clock network (Figure 7). The SCN is the master conductor but each organ has its own clocks with its own set of genes and proteins. When they are turned on and off at a time that is in sync with the SCN all is well. But when they are out of phase there may be ill health or disease.

In addition to light, which is the major regulator of the clocks, eating (which involves the GI track including the pancreas and liver (see below) is also a major regulator and there may be problems when the sleep-wake clock and the food digestion clocks are off schedule. The same is true of the immune system, muscle strength, heart action, etc. Shift workers have been recognized for some to have a higher rate of a number of diseases and disorders. (See an earlier blog “Sleep 2020”). This almost certainly has something to do with their “unnatural” chronobiology. There is a clear link in shift workers to type 2 diabetes, weight gain, coronary artery disease, stroke and certain types of cancer.

And what about the long-distance solo sailors – and I am thinking here of the recent Vendee Globe 2020-2021 race. There were 33 starters on 8 November 2020 and the first finishers completed the course on 27 January 2021. The last arrived 5 March 2021. We do know from prior races of this kind that certain “chronotypes” e.g., the “night-owls” do not compete, so there is a self-selection process going on.

Nevertheless, there is no way to prepare for the constant sleep deprivation and clock network disruption when you are catching 20-minute naps throughout a 24-hour period. The pacemaker SCN clock and all the various organ clocks in Figure 7 must be going into quiet rebellion.

Figure 7: The SCN Pacemaker Clock and organs with their own clocks forming an integrated network. If you look at the "Molecular Circuitry" you can identify PER which is the Period gene, the one that we share with most other animals including the lowly fly! Yeah, it’s complicated. “Circadian Mechanisms in Medicine”: New England Journal of Medicine volume 384, no.6 p. 550-561, February 11, 2011

I doubt that 2 ½ or 4 months are going to cause permanent health problems. However, armed with this information I believe it is fair to say the following: this race, a solo around-the-world, non-stop race is an ultimate human challenge. Not only is the sailor competing against fellow racers, the weather, and the integrity of their boat but these men and women are actually competing against their own body. It is not merely overall endurance; but rather each organ is on its own clock time schedule trying to take care of business – this must be one of the most grueling athletic feats imaginable!

Chronotherapy on the Water

Before leaving the issue of circadian rhythm, I would like to introduce something most have never heard of (and I was unaware of it until just a few years ago) – chronotherapy. It is a new and evolving field based on the premise that administering medications at different times of the circadian cycle will minimize side effects and maximize therapeutic effects. It is something sailors should be aware of since they are often on a rotating shift if there is a limited crew or significant duties as in the navy.

First studied in cancer treatment, it was found that cancer chemotherapeutic medications have greater effect and less side effects when administered at a specific time each day.

When I became aware of the field a couple of years ago, I researched the medications I was taking for hypertension and elevated cholesterol. I had been on these medications for 30 years and for all those years I was taking both in the morning. To my surprise, I discovered that best results are achieved if taken at night. [Better late than never, I suppose]. If you are on medication you should do a little personal research since it is quite likely that your personal physician is unaware of the issue. It also applies to supplements you may be taking [although as discussed in the book, most supplements not given for a specific condition are just throwing money away. Save your money and upgrade your electronics instead.

Nautical Time or “what did you say the time is, sailor?”

Nautical time was devised to allow ships on the open ocean to express a local time. Nautical time zones are split into one-hour intervals for every 15 degree change in the ship’s longitude. It is typically used for oceanic travel as captains will usually avoid changing the timekeeping over short distances such as in inland seas or channels.

Figure 9: World Time Zones with Labels A through Z (NIST)

Figure 10: World Time Zones with times based on Greenwich “Noon”

Figures 9 and 10 represent maps of all of the world time zones. All times begin at Greenwich which is represented as “0” hours at the bottom on both. New York for example is -5 hours from Greenwich: if it is noon in England it is 7am in New York.

Nautical standard times, time zones and even the nautical date line are the result of the Anglo-French Conference on Time-keeping at Sea in 1917. [6] A letter suffix was added to the time zone description assigning “Z” to the zero zone (including Greenwich) and A-M (except the “J”) to the east and N-Y to the west. M and Y have the same clock time but differ by a full 24 hours. Each of letters is assigned a phonetic name as seen below in Figure 9.

The letters at the bottom are the time zone names and are normally named Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo, Foxtrot, Golf, Hotel, India, Kilo, Lima, Mike, November, Oscar, Papa, Quebec, Romeo, Sierra, Tango, Uniform, Victor, Whiskey, X-ray, Yankee, Zulu.

That’s how we get “Zulu” time. [7]

Before we go any further, we should remind ourselves of the differing terminology of civilian time and military time. Most of you will be more or less familiar with the conversion which eliminates duplicate numbers for AM and PM. Below is a standard civilian to military time conversion chart. [8]

Figure 11: Military to Standard (Civilian) Conversion

Nautical time zones are used by the military to ensure a standardization of time for the forces. Standard military orders would be delivered in Zulu time. Zulu time is the same as "Greenwich Mean Time" or GMT. Depending on the ship or unit’s location on the planet, it will determine the amount of offset required. For example, if the orders were to launch a mission at 1000 Zulu, and your ship was located near Tokyo, Japan in the "India" time zone -- the India time zone is GMT plus nine hours, so you would add nine hours to 1000 Zulu, and know your time to launch would be 1900 local time (India). [9] Here is another example: For instance a flight may be listed to leave deck at 0300Z (1400L), which would mean the plane is taking off at 3:00 am Greenwich mean time, which is at 2:00pm local time, (the L is for Lima time zone). Since operations often take place across multiple time zones, using one consistent time zone reference is useful for coordination.

So Zulu time is Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) but what exactly is GMT? GMT is actually an archaic term which now is really just another name for the time zone. In the year 1884, longitude zero was defined as the longitude of the Greenwich observatory. And prior to 1972 it was the de facto standard but has been replaced by UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) the successor to GMT.

Let’s start by looking at GMT as it was defined before Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) [10]came into use. GMT is short for Greenwich Mean Time. The word “mean” here equals “average”. GMT is actually the mean solar time at Greenwich (in London, England) (Figure 12).

Figure 12 This is the Prime Meridian of the World. All time and longitude is based on this meridian. You can step on either side of the Prime Meridian and have one foot to the east and one to the west. I was at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich in Y2K.

Solar time is based on the apparent movement of the Sun across the sky. It depends on the rotation of the Earth and, to a lesser extent, the Earth’s orbital motion around the Sun. Because of the Earth’s axial tilt and its elliptical orbit there are daily variations in the position of the Sun in the sky. For convenience, the variations are averaged out by using what’s called mean solar time. That uses a “fictitious” Sun which moves at constant speed.

The length of a mean solar day is 86,400 seconds. That's 24 hours of 60 minutes, each with 60 seconds. These seconds are mean solar seconds.

UTC uses a slightly different second called the SI second. That is based on atomic clocks. Atomic clocks are more regular than the slightly variable Earth's rotation period. Hence, the essential difference between GMT and UTC is that they use different definitions of exactly how long one second of time is – celestial movement versus the more recent and accurate atomic clocks (see below). [11]

The UTC day length is 86,400 SI seconds. The mean solar day is 86,400 mean solar seconds. That’s 86,400.002 SI seconds. That small difference in the day lengths is slowly increasing as the rotation period of Earth slowly increases.

GMT is now best used to refer to the GMT time zone rather than as a measurement of time itself, but it's still sometimes used in the original sense.

GMT (in its original meaning) is basically synonymous with UTC, because the difference between them is so small.

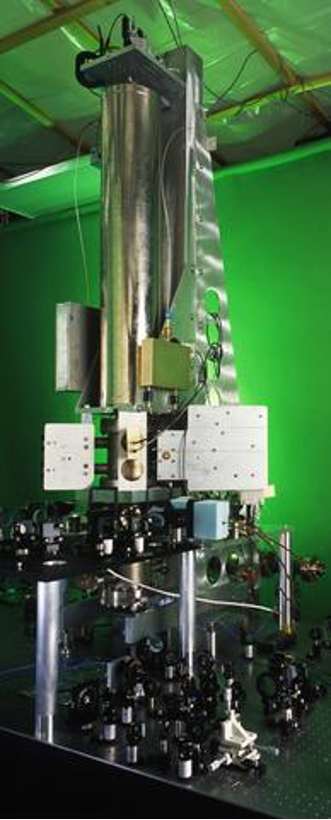

In the US, the primary time and frequency standard is the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) NIST-F1. It contributes to the international group of atomic clocks that define Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), the official world time. Since NIST-F1 (Figure 13) is among the most accurate clocks in the world, it makes UTC more accurate than ever before.

Figure 13: NIST-F1 Atomic clock, Boulder Colorado

The uncertainty of NIST-F1 is continually improving. In 2000 the uncertainty was about 1 x 10-15, but as of January 2013, the uncertainty has been reduced to about 3 x 10-16, which means it would neither gain nor lose a second in more than 100 million years! [12]

What Time is “Ship Time”?

A captain is permitted to change his or her clocks at a chosen time following the ship's entry into another time zone. The navigator often decides, subject to the CO’s approval what day and time to shift the clocks. Ships do a time check every day at sea, usually about 0800. When a time change is done it is announced and there is a new time check and new time zone time if applicable.

Ships on long-distance passages change time zone on board in this fashion. On short passages the captain may not adjust clocks at all, even if they pass through different time zones, for example between the UK and continental Europe. Passenger ships often use both nautical and on-board time zones on signs. When referring to time tables and when communicating with land, the land time zone is usually employed.

Submarines apparently stay on Zulu (GMT) for most or all of the voyage until the sub ties up back in port. In port the crew could set their personal watches to local time but the boat stays on Zulu time.

Cruise ships

Most of the ships will change time in a fashion which gets them to the time zone of the next port with the fewest time changes. This often means not strictly adhering to the times of the intermediate time zones, especially on transpacific voyages crossing the International Date Line. For instance, when traveling from the US west coast to Asia, the ship may retard clocks 1 hour each night for 8 or 9 nights (depending on daylight savings time) then skip 1 day. This has the effect of advancing the 16 (or 15) hours needed to get on Asia time. Coming back the ship will advance the 8 or 9 hours, sometimes 1 hour a night but more frequently 3 hours a day, then repeat 1 day.

You must pay special attention to time, especially in the Caribbean. Whatever you do, don’t depend on a fellow cruise-mate as he or she will probably be inebriated. [“Ship Time” has a double meaning. One the one hand it represents the time that is carried on the ship. On the other hand, every time is “Ships Time” if you know what I mean.]

This is from the web site “This is Cozumel” (accessed 6 April 2021).

If you're arriving on a cruise ship then understanding the difference between ship time and local time can be very important, especially if you book one of our Cozumel shore excursions.

The south-east of Mexico, including Cozumel, is in a special time zone that does not change the clocks for Daylight Saving Time in the spring or fall. This affects the time difference between Cozumel and the U.S., Canada, and other parts of Mexico, as well as cruises' onboard "ship time" in some cases.

Different cruise lines have different ways of deciding what time their ships take. Carnival and Royal Caribbean (RCCL) cruise ships usually go with the time of their homeport and stick with it, whereas Norwegian cruise ships change their onboard time during the voyage, to match the local port they are arriving to.

The itineraries cruise lines give passengers display ship times, so cruisers should remember this isn't necessarily the same as the local Cozumel time.

Cozumel is on U.S. Central Time from March 10 to November 2, 2019 (during U.S. Daylight Saving Time) but then will be on U.S. Eastern Time from November 3, 2019 to March 7, 2020 (during U.S. wintertime). Peruse this chart to get an idea how careful you must be going or coming from port.

I think you get the idea! I leave you with these:

“A stitch in time saves nine” and “Procrastination is the thief of time”

[1] In case you have ever wondered why time is not “metric” like the rest of science (and in fact the rest of the world except for the US and two tiny countries) this is why. If time is passing too fast or too slowly for you blame the Babylonians, it’s their fault!

[2] For those of you who have read Chapter 12 there is some overlap with being in a “flow” state. Both Plato and Aristotle wrestled with the problem of time. Aristotle viewed time as motion. Plato argued that time began with the creation of the universe.

[3] See “Your Brain is a Time Machine” by Dean Buonomano, a wonderful and comprehensive look at the problem of time. Highly recommended.

[4] Those darn Babylonians again with their “sexagesimal” system – based on the number 60

[5] But by the mid-19th century not everybody was pleased with the situation. “Lieutenant Davis of the U.S.Navy suggests, ‘Hitherto we have used the English Meridian of Greenwich; all our astronomical calculations are fixed according to that, our nautical charts are adapted to it, and our chronometers are set to its time. The scientific importance of assuming an American Meridian is undoubted.’ So long as we depend upon that from which we are separated by an ocean, our absolute longitudes remain indeterminate. There is no place on our coast, the longitude of which from Greenwich is so well ascertained as Boston. Yet there still exists an uncertainty in this longitude, of perhaps two seconds of time.” Scientific American, September 1849

[6] See Wikipedia “Nautical Time”

[7] Interestingly Romeo gets a time zone, but Juliette is conspicuously absent although both committed suicide. Sexist? You decide. The J for Juliette is sometimes used for local communications.

[8] The United States military uses a 24-hour clock to save confusion. There are not two "four o'clocks" in military time as there is with civilian time. The civilian 4:00AM is equal to 0400 (Zero four hundred) and 4:00PM is equal to 1600 (Sixteen hundred) military time. A couple more examples of local time conversion and how to speak it: if local time is 9:27 AM, the local military time would be 0927, and it would be spoken as "Zero nine twenty seven." If the local time was 7:36 PM, the local military time would be 1936, and it would be spoken as "Nineteen thirty six." When message traffic is sent, each message receives a Day Time Group (DTG). The DTG has the day, month, year, and time the message is logged. For example, a message's DTG may say, 212200Z May 2013. Broken down, you know the message was logged on May 21, 2013 at 2200 Zulu time. © NCCM Thomas Goering USN (RET) Navy CyberSpace.

[9] www.navycs.com/militarytime.html

[10] Why is Coordinated Universal Time called UTC not CUT: In English, the abbreviation would be CUT. The equivalent French abbreviation would be TUC. UTC was chosen as a compromise.

[11] Then there is Universal Time 1 (UT1) which measures the Earth’s rotation with respect to the distant stars (or more recently quasars). There are exactly 86,400 UT1 seconds in a UT1 day.

TAI (International Atomic Time) which measures time according to a number of atomic clocks. There are exactly 86,400 TAI seconds in a TAI day..

A UTC second is by definition always exactly equal to one TAI second, but like the old GMT, a UTC day is not necessarily 86400 seconds long. The difference between the old GMT and UTC is that in lieu of the small daily adjustments used in the now deprecated GMT, the adjustments to UTC are infrequent and are always exactly one TAI second. These are leap seconds. The predictability and the current close match between UT1 and TAI means that leap seconds can be announced well in advance, only have to occur on June 30 or December 31, but can still keep UTC and UT1 within 0.8 seconds of one another.

[12] https://www.nist.gov/pml/time-and-frequency-division/time-realization/primary-standard-nist-f1